CLIMATE

CHANGE IN WALES -

A GEOLOGIST'S PERSPECTIVE

PART 1: EXAMINING THE PAST

BACK TO WEATHER-BLOG MENU

New! Fine Art Prints & digital

images for sale-

Welsh Weather & Dyfi Valley landscapes Slide-Library

- Click HERE

Climate change (impact

definition): Change of the climate system that is faster

than the adaptation time of social and/or ecosystems.

11,500

years ago we finally came out of the last glaciation, or

ice-age. This had lasted for over 100,000 years, during

which ice-caps formed over the Welsh mountains, covered

the Irish Sea and extended southwards almost into South

Wales.

This was but one of several lengthy glaciations within

the Pleistocene, a division of geological time that began

a little over 1.8 million years ago. Prior to that, the

climate had been considerably warmer for some time....

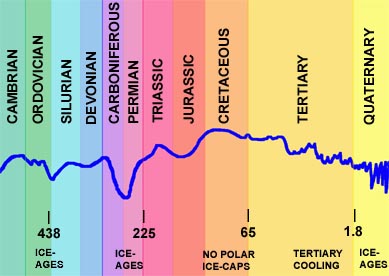

This graph shows average global temperature changes (blue line) through the last 500+ million years. The geological timescale is not proportional, in order to fit in the more detailed data over shorter timespans that is available in geologically more recent time. Some key dates (in millions of years ago) are inserted below the blue temperature plot. The science of interpreting ancient climates is known as palaeoclimatology. The evidence sought after is in the form of fossil faunas and floras which may be interpreted to reconstruct ancient ecosystems - for example, extensive shallow-water coral-reefs are indicative of a warm climate. Coupled with data which allow reconstructions of the positions of the continents relative to the Earth's poles, and hard geological evidence such as tillites (sedimentary rocks deposited by ice-flows), it has been possible to construct a view of what the climate was like going back many millions of years.  Above: a reconstruction of the positions of some of the continents, 495 million years ago, when the UK was not only south of the Equator but split in two with an ocean in between! The continental collision that brought the two halves together forced up the range of mountains that includes Snowdon, Scafell and Ben Nevis. Due to the fates and fortunes of continental drift, Wales was pretty much unaffected by the earlier glaciations during the Ordovician and Permo-Carboniferous. It was still situated in the tropics....  Above: the cliffs at Lavernock, on the Bristol Channel in South Wales, record the time when Wales was an arid desert in the Triassic Period. The rocks here are red marls, with bands of the mineral gypsum. They were formed in a desert plain in which saline lakes temporarily appeared and evaporated. It can be difficult to imagine geological timescales and the vast changes that happen within them. One has to combine the geological evidence available with the imagination of the mind's eye. I have had a go at describing what the view might have been like from Plynlimon in Central Wales during the Triassic: "It is a fine summer day and we stand on the summit of Plynlimon looking at the strange landscape through the heat-haze. To the north and the south low undulating hills stretch into the far distance. To the west the hills tail off into a great depression where Cardigan Bay ought to be. There is not a sign of life in this silent red land. The open sea lies a long distance off to the north and east, beyond the salt-lagoons of the Cheshire Plain. The seemingly endless cycle of sunrise and sunset over the red landscape will continue for another ten million years. It will take that long for the sea to return." The tropical odyssey continued until Wales, along with the rest of Europe, began to drift northward in the aftermath of the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea, which got underway in the Jurassic Period....  Above: the southern part of the Northern Hemisphere in Jurassic times, just after Pangaea started to break up. During Cretaceous times, the global climate was stable and considerably warmer than that of today, especially in the higher latitudes. Geological evidence suggests that there were no permanent polar ice-caps present for a period exceeding 40 million years. The situation continued through into the early part of the Tertiary Period, seemingly unaffected by the K-T mass extinction event, but by mid-Tertiary times a progressive cooling was underway.  Above: by Miocene times, Europe was a more familiar shape, although Italy was yet to dock with the rest of the continent. The collision, later in the Miocene, caused the mountain-building events that resulted in the formation of the Alps. By the start of the Pleistocene, the Earth had begun to experience a series of cyclic, violent climatic oscillations, each involving a slower cooling to a lengthy glaciation followed by a sharp warming into a shorter interglacial period, where the climate was similar to, or slightly warmer than, that of today. We are now within such an interglacial episode. |

|

The

current interglacial is referred to as the

Holocene and is the most recent division of

geological time. The last glacial episode started

to retreat in earnest 14,500 years ago, but was

interrupted by another cooling phase and slight

readvance of ice. This is known as the Younger

Dryas, and its end marks the Pleistocene-Holcene

boundary. The rate of warming that ended the

Upper Dryas was extraordinary: analyses of

ice-cores have indicated rises of 10oC

in as little as a decade!  Above: the beach at Tonfanau, on the Cardigan Bay coast, consists of extensive boulder-fields interspersed with small patches of sand. Many of the boulders are rock-types that do not outcrop on mainland Wales. They were dumped here by the ice-sheet that flowed down the Irish Sea, and were either ripped up from what is now the sea-bed of Cardigan Bay or were transported from even further afield by the ice. The sudden warming was interrupted at times. A cooling event well-documented from ice-cores occurred 8200-8400 years ago and the effects were many years of cool dry conditions across the Northern Hemisphere; a second event 6000 years ago had serious ecological effects in the Sahara area where dry conditions encouraged major desert expansion over what had previously been a fairly well-vegetated landscape. More recently, we have the cooling known as the "Little Ice-age" which brought to an end warmer conditions experienced in Medieval times. The cooling began in the 1400s and ended in the 19th Century. Now, the second part of this account looks at the current warming, and examines its potential effects in the context of what we know about the past. PART TWO |

|

BACK TO WEATHER-BLOG MENU New! Fine Art Prints & digital images for sale- Welsh Weather & Dyfi Valley landscapes Slide-Library - Click HERE |